The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has reclassified some of its paintings, including two artists previously labeled as Russian, now categorized as Ukrainian. In addition, a painting by the French Impressionist Edgar Degas has been renamed from “Russian Dancer” to “Dancer in Ukrainian Dress.” For Oksana Semenik, a journalist and historian in Kyiv, Ukraine, these changes represent a form of vindication. Semenik has been campaigning for months to persuade US institutions to relabel historical works of art that she believes are wrongly presented as Russian, including pieces by Ilya Repin and Arkhip Kuindzhi. Despite being born in Ukraine and depicting Ukrainian scenes, these artists were previously categorized as Russian due to the region’s inclusion in the Russian empire at the time.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has updated its catalog to reflect that Ilya Repin, a celebrated 19th-century painter born in present-day Ukraine, is “Ukrainian, born Russian Empire.” Descriptions of his works now begin with the statement, “Repin was born in the rural Ukrainian town of Chuhuiv (Chuguev) when it was part of the Russian Empire.” Oksana Semenik, who runs the popular Twitter account Ukrainian Art History with over 17,000 followers, noted that Repin’s paintings mostly depicted Ukraine, particularly its landscapes, the Dnipro river, the steppes, and the Ukrainian people.

Arkhip Kuindzhi, a lesser-known contemporary of Repin, was also born in Mariupol in 1842, during a time when the city was part of the Russian Empire. His nationality has also been revised, and the text describing his painting “Red Sunset” at the Met now acknowledges that the Kuindzhi Art Museum in Mariupol was destroyed in a Russian airstrike in March 2022. The Met stated that they continuously research and examine objects in their collection to ensure that they are accurately cataloged and presented. Scholars in the field were consulted during the research process that led to the recent relabeling of these works. When asked about the renaming of the Degas painting to “Dancer in Ukrainian Dress,” a spokesperson told Semenik in January that they were collaborating with scholars to determine the most appropriate and accurate way to present the work and appreciated feedback from visitors.

According to Oksana Semenik, she utilized her frustration with the Russian invasion as motivation to promote and identify Ukraine’s artistic heritage. Through her Twitter account, Ukrainian Art History, she has been showcasing Ukrainian art to the world. Semenik was fortunate to survive the Russian assault, which destroyed the area where she was staying in the Kyiv suburb of Bucha. She and her husband, along with their cat, sought refuge in a kindergarten basement for several weeks before embarking on a 12-mile journey to safety. Semenik began her campaign after assisting curators at Rutgers University in New Jersey and discovering that artists she had always considered Ukrainian were labeled as Russian.

Oksana Semenik discovered that many Ukrainian artists were included in the Russian art collections after researching them. “Of the 900 artists considered to be Russian, 70 were Ukrainian, and 18 hailed from other countries,” she stated. Semenik studied collections at the Met, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and in Philadelphia, discovering a similar trend of Ukrainian artists and scenes being labeled as Russian. She began writing to museums and galleries, but initially received non-committal, pro forma responses. “I became increasingly frustrated,” she said. This led to a months-long dialogue with curators.

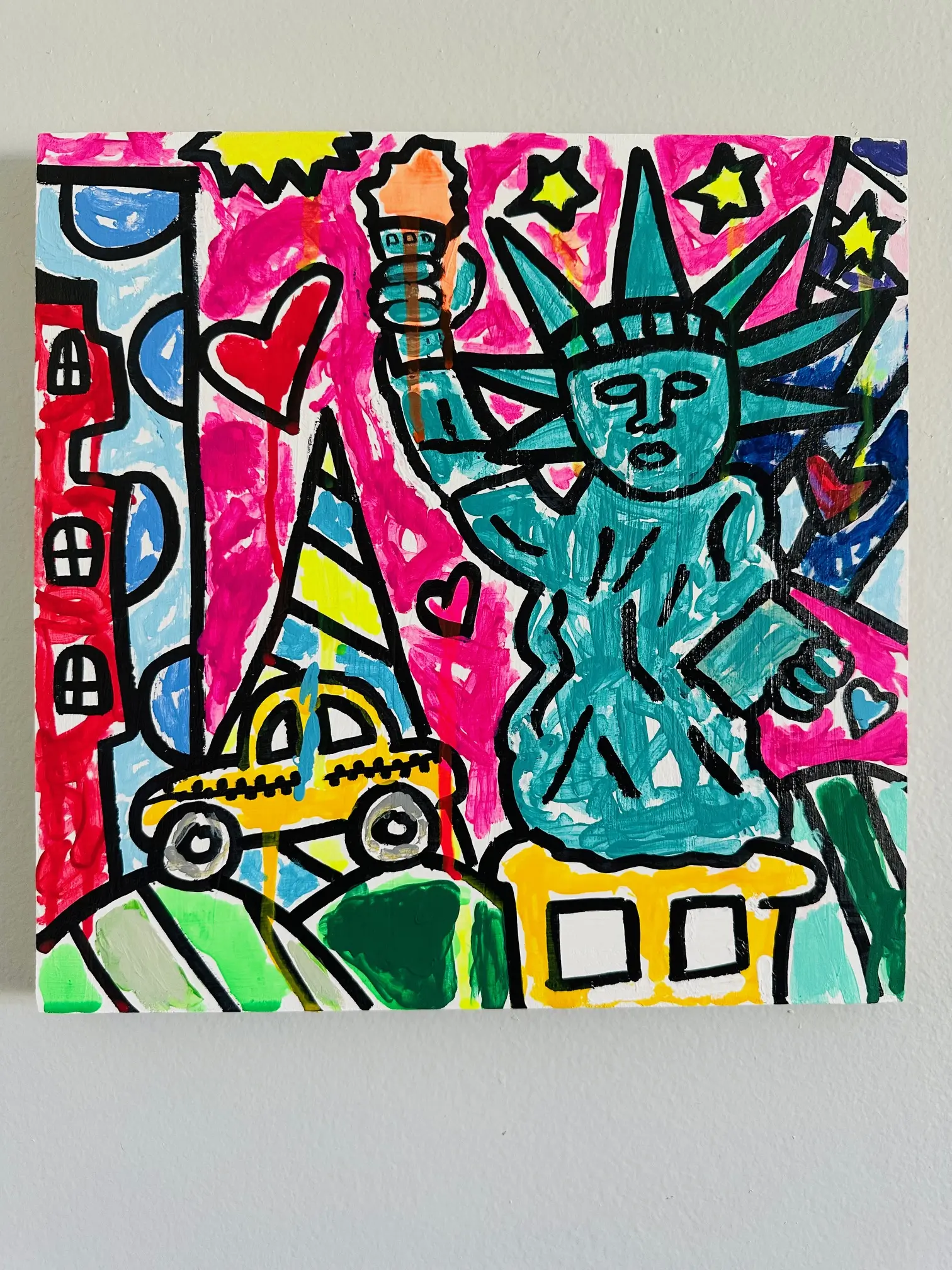

Semenik’s calls for change have been echoed by other Ukrainians. In an article for German newspaper Der Spiegel last year, Olesya Khromeychuk, whose brother died fighting on the frontline in eastern Ukraine in 2017, stated, “Every visit to a gallery or museum in London with exhibits on art or cinema from the Soviet Union reveals a deliberate or lazy misinterpretation of the region as one endless Russia; much like the current president of the Russian Federation would like to see it.” As a result of pressure from numerous Ukrainian academics, the National Gallery in London changed the title of Edgar Degas’s “Russian Dancers,” a painting depicting two women in yellow and blue ribbons, the colors of Ukraine’s flag, to “Ukrainian Dancers.” According to the Guardian, the institution claimed that “it was an appropriate time to update the painting’s title to better reflect the subject of the painting.”

Semenik, is currently continuing her efforts to persuade the Museum of Modern Art in New York to revise its labels. In response to her campaign, a spokesperson for the museum stated that they appreciate any information related to the works in their collection. The spokesperson explained that determining an artist’s nationality can be a complex process, particularly in cases where attributions are made after the artist’s death. The museum applies rigorous research methods and takes into account various factors such as the artist’s nationality at birth and death, as well as historical changes in geopolitical boundaries and emigration/immigration patterns.

Alexandra Exter, another Ukrainian artist, is listed as Russian on the MoMA website. “She lived in Moscow from 1920 until 1924. She lived In Ukraine from 1885-1920, which is 35 years and in France for 25 years. “Why on earth is she Russian?” she said. Semenik’s tireless efforts to reclaim Ukraine’s artistic heritage from the shadow of Russia are not just a matter of national pride; they are a critical part of the struggle for independence and cultural autonomy. As she continues to fight against the erasure of Ukrainian artists and their works, Semenik reminds us that the power of art is not just in its beauty or its ability to inspire, but in its ability to challenge and subvert dominant narratives. The question remains: how many more Ukrainian artists must be mislabeled and erased before the art world wakes up to the cultural theft taking place right under their noses? Semenik’s work is not just an act of resistance, but a call to action. It is time for the world to recognize and celebrate Ukraine’s rich artistic heritage, and to stand in solidarity with those who are fighting to preserve it.