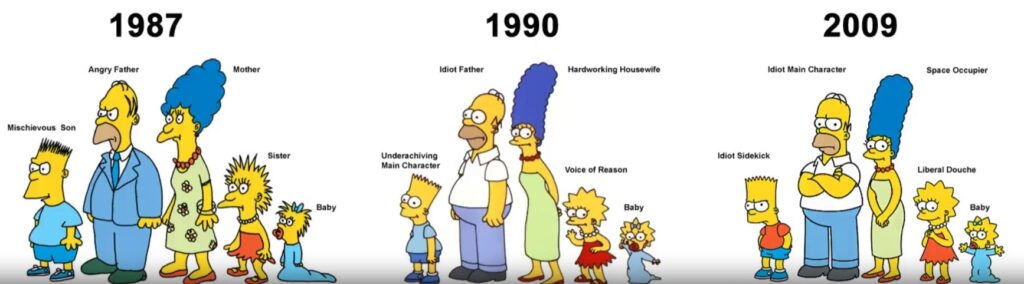

In 1996, The Simpsons surpassed The Flintstones to become the longest-running prime-time animated show, marking a significant shift in the tenor of adult cartoons. While The Flintstones was a shameless remake of a popular 1950s sitcom, The Honeymooners, The Simpsons was more caustic and puerile. However, despite these differences in tone, the creative process remained largely unchanged. Like The Flintstones, The Simpsons relied on a team of writers, directors, storyboard and design artists, and animators, with the main difference being that the final stage of animation was outsourced to South Korea.

A year after The Simpsons overtook The Flintstones, South Park premiered, heralding a new era in fast and cheap animation that was able to comment on current events. This, coupled with the rise of computer animation and the internet, has made animation faster, rougher, and looser. However, The Simpsons has remained steadfast in its adherence to a lengthy and expensive production process, making it an outlier in the world of animated TV.

Currently in its 27th season, The Simpsons follows a meticulous and detailed process in creating each episode. It all starts with a retreat where the writers come together with their pitches, and after receiving feedback from the show’s creators, they proceed to break scripts in the sterile writers’ rooms of the Fox studio lot.

Despite the evolution of animation techniques, The Simpsons remains one of the few shows that embraces traditional formulas dating back to the days of Walt Disney and Hanna-Barbera. While shows like South Park can now be created in a week with a small team, The Simpsons has added more roles and failsafes to its already lengthy process. All in all, The Simpsons remains a high-touch, slow-paced production that continues to build upon its bedrock with the tools and lessons of the future.

Creating An Episode of The Simpsons

The Simpsons production process is all about maximizing efficiency and utilizing more resources. With more people involved, more jobs are completed with more failsafes, but at a higher cost compared to other animated TV shows. The writer of an episode has two weeks to create a first draft, which is then reworked by a team of writers in one of two rewrite rooms on the Fox lot. This change in the writing process occurred around season nine due to having enough writers to split into two rooms. The rewriting process takes up to four to six weeks, with constant feedback from showrunners Al Jean and Jim. While the completed script serves as a guide, it is not a rigid blueprint. It is subject to change and revision, with additional support from the rest of the production team as needed.

On a weekly basis during production, the writers, producers, and cast gather for the table read of the latest script. While some cast members attend in person, others join remotely. In certain cases, Chris Edgerly, who has been responsible for “additional voices” on the show since 2011, substitutes for one of the leads. According to Jean, it is rare for all of the actors to be present due to scheduling conflicts and relocations.

Despite attending hundreds of table reads, Al Jean remains uncomfortable with the process. He explains that the table read is a crucial phase in which the creative merit of the script is assessed while also being subject to external influences. Interruptions such as a ringing cell phone or a sick actor can shift the mood of the session. “Last week,” Jean recalls, “a reversing truck came in the middle and distracted everyone. The table read is my least favorite part of the process.”

The voice recording session takes place on the Monday following a table read, usually at the LA studio. Instead of recording together, each actor and actress records their lines separately, which is a common method for voice-over work. Al Jean finds it amusing that a review in The AV Club once praised the interaction between two actors in a show who never actually met while recording their lines in different locations. He is glad it worked out, but notes that there was no physical connection.

As the work shifts from script to animation, the episode is handed over to a director who takes ownership of the production and animation responsibilities. Al Jean compares this role to that of a TV director who directs an episode based on a script. However, the Simpsons director has to create everything from scratch. The director supervises the design, motion, acting, and visual aspects of the episode using the audio track and works in tandem with Al Jean, the story liaison, to guide the script through the animation process.

The animation phase of a new season of The Simpsons typically starts between February and April, depending on various production variables, as stated by veteran storyboard artist Luis Escobar. Some animators have breaks between seasons while others move directly from one season to the next.

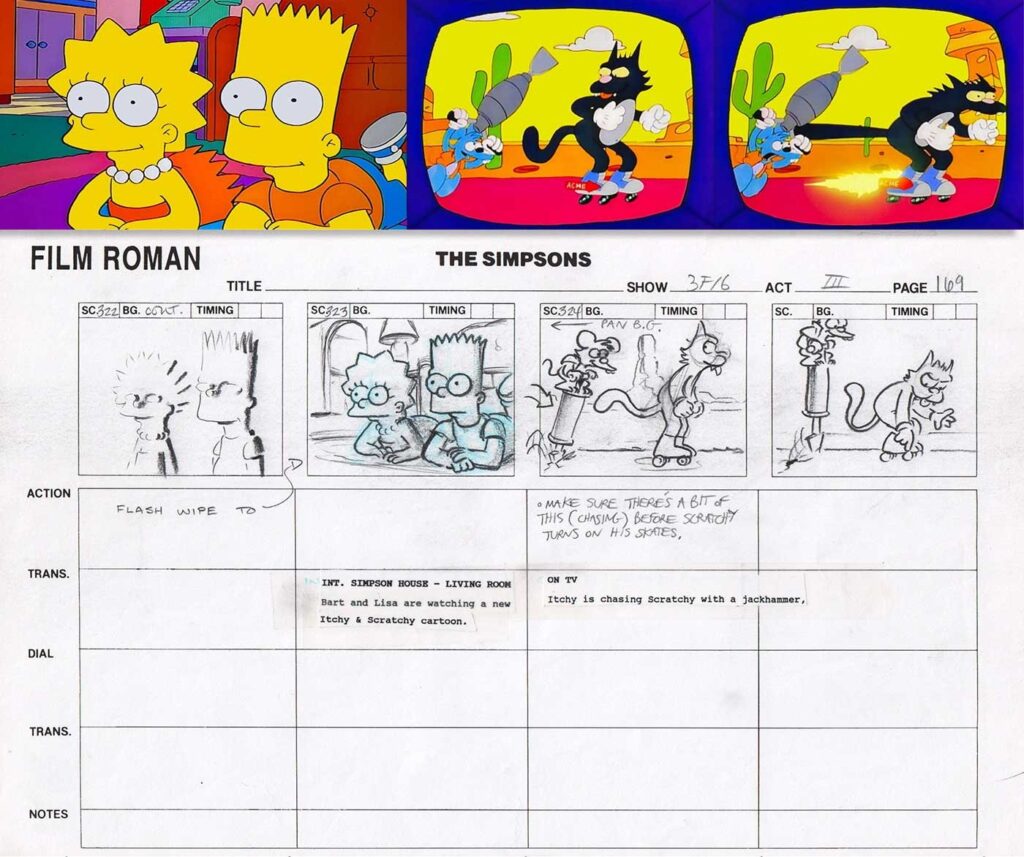

Storyboarding The Simpsons

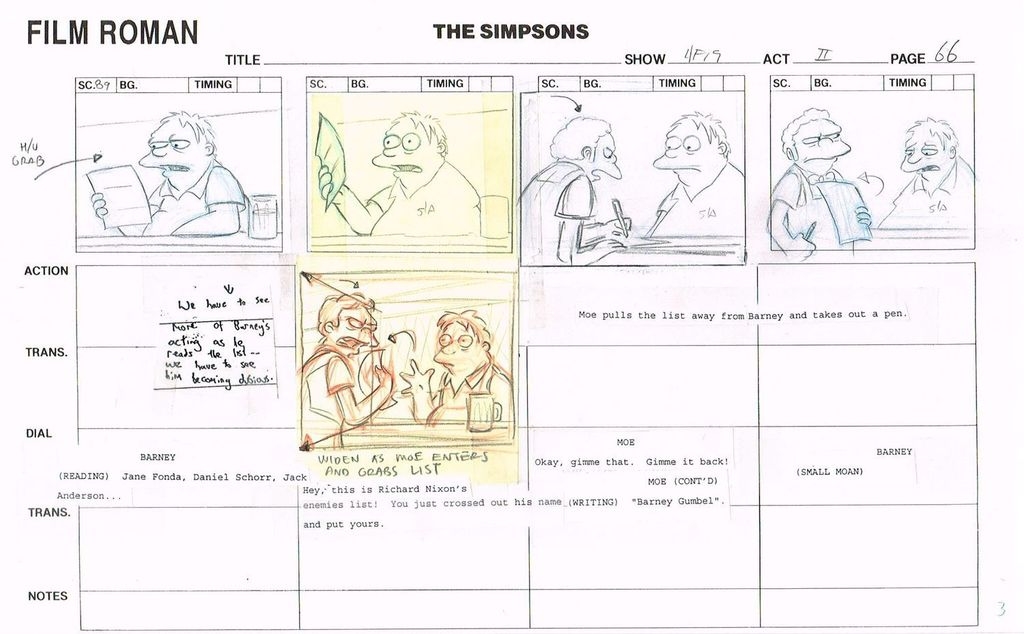

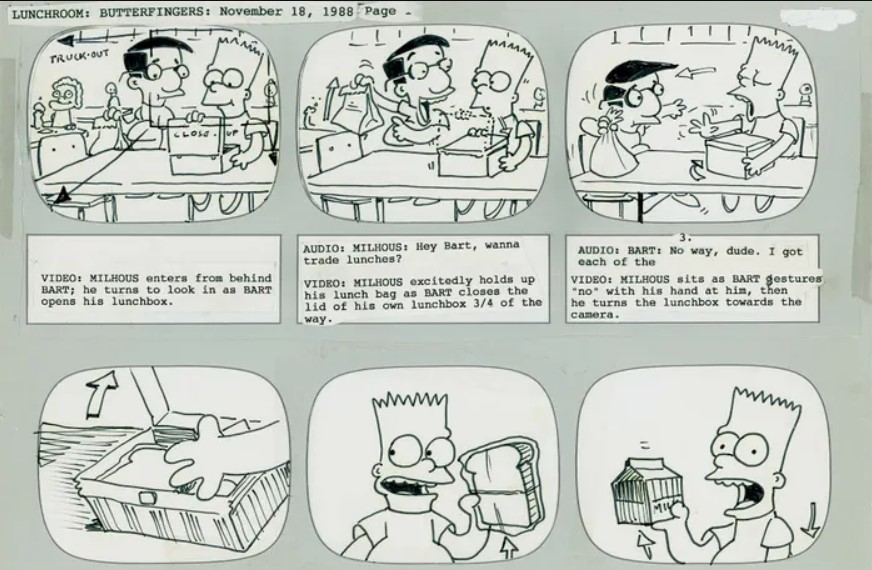

Storyboarding is the first step in the episode’s animation process, which includes multiple stages and results in materials that South Korean animation studio Akom will use to complete the episode. According to Escobar, the initial storyboard artists, assigned to a small group at The Simpsons’ Southern California workspace, are responsible for planning, designing, and conceptualizing the episode, creating a blueprint for what it will eventually look like.

After the storyboard is completed, it is reviewed, revised, and sent to Fox for additional feedback. Additionally, a group of designers creates props, characters, and backgrounds unique to the episode, which also undergo a similar process of drafts and reviews.

In the early seasons, storyboarding was done on paper, but the show later switched to animatics, a series of images paired with the voice track, which would be edited on tapes. Recently, the show has transitioned to digital storyboarding, where all art and audio are uploaded to an online hub that can be accessed from any computer or smart device.

Making Changes Working Remotely

Thanks to this change, Jean can now edit audio from his phone instead of visiting an editing bay, and video effects can be made with a few digital tweaks, rather than requiring portions of the storyboard to be completely redrawn. Throughout the animation process, Jean, who serves as a story liaison for the entire series, and each episode’s director work together to ensure that the script is brought to life through animation.

The Simpsons production process no longer includes the story reel role, which used to be a separate step before storyboard revisions. Nowadays, the storyboard and story reel processes are combined, and the revised storyboard is directly used to create the final episode. However, in the past, after the storyboard was revised based on Fox’s notes and accompanied by the voice track, it was screened to story reel artists who were assigned a portion of the episode to work on.

The reel artists added additional character poses, cleaned up backgrounds, and incorporated notes from the director to refine the composition of the shots. Once the work was completed, it was uploaded to a server and the editor inserted the fleshed-out segments in place of their respective portions of the storyboard, replacing the entire storyboard with a completed story reel.

The story reel, which ideally played like a barebones, black-and-white version of the actual episode, was then screened to shareholders, including Al Jean and the producers, writers, and episode director, for feedback. The shareholders took notes, discussed what worked and what didn’t, and pitched additions or changes they wanted to be made. The team then watched the episode again, stopping and starting the reel to discuss how the changes would be incorporated, sketching rough stills of what the changes should look like, and finalizing any other tweaks to be made by the storyboard revisionist.

Storyboard revisionists had about two weeks to revise or create new scenes based on notes from the previous screening. They salvaged parts from scenes that were cut by repurposing them within the revisions and made sure the changes flowed with the rest of the story reel. Sometimes, they had to figure out how to resolve continuity issues, like when a character needed to be on the other side of the room but no longer had the line that made them walk over there. In such cases, a quick reaction shot of another character was cut to, then back to the original character who was now magically on the other side of the room.

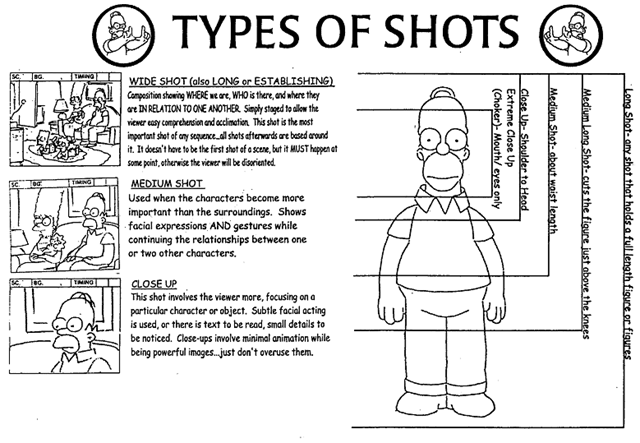

Escobar notes that few American animated shows still follow the layout process, let alone perform it in-house. However, layout is considered the phase that most resembles what a layperson would imagine animation to be, such as a classic Disney cartoonist sketching characters into motion. At The Simpsons, the layout process is a digitized version of this method, where each animator, divided into character and background artists, uses Pencil Check Pro to animate roughly 15 scenes per episode, creating an accurate depiction of the final product. While storyboards are rough, layout is a refined stage that involves matching characters to a model sheet that includes established poses and expressions.

Laying Out The Art

The layout artist’s primary function is to imbue the static storyboard images with performance by deciding precisely how the characters will look and emote, doubling as actors to achieve this effect. The layout artist also frames shots like a real camera, which is essential as everything they draw will be incorporated into the final “clean line” version of the episode animated in South Korea. Story layout is the most extended and detailed step, taking anywhere from a month to a month and a half, depending on the episode’s complexity and the presence of other episodes in production. After finishing a scene, the character layout artist delivers it to the timer, who writes exposure sheets, the notes for Akom on how to interpret and apply the work of the story layout artist.

This process involves breaking down all dialogue and animation, assigning tiny pieces to specific frames of the episode. The timer writes dialogue phonetically and establishes mouth shapes that match each sound onto the exposure sheet, along with any specific accents or flourishes that need to be made to the character’s face or body. The timer also adds any touches not included in the digital animatic, ensuring maximum control over what the South Korean animation studio delivers.

Scene Planning is responsible for digitally animating complex scenes in which multiple characters are featured in large-scale, fast-moving actions. This internal team was formed after the production of The Simpsons Movie. Peter Gave, a production member, takes charge of the digital character layout scenes and prints them on paper to be shipped to South Korea. Despite the artwork being digital, they must conform to actual paper field sizes.

Two checkers review all aspects of the artwork and exposure sheet to ensure consistency and accuracy. They act as spell checkers and grammar reviewers for the animation, and if they find any inconsistencies or errors, they report them to the director for correction. Once the entire episode is checked and approved, it is sent to South Korea.

Akom Studios and The Simpsons

Akom, a South Korean animation studio located west of Seoul, is responsible for animating the frames between the drawings in the final reel delivered by the layout artists for The Simpsons. For example, if the layout artists animated 20 frames for a 3-second scene, Akom would need to create a clean line version of the original 20 frames and the 52 frames of animation between them, as the sequence is 72 frames long at 24 frames per second. This process is called overseas export market work, and Akom is one of many OEM studios in South Korea.

Since 2005, Akom has handled the final and significant phase of animation for The Simpsons, which involves roughly 120 animators and technicians translating the storyboard and layouts into the completed rough edit of an episode, taking about three months depending on the episode’s complexity and position within the season. While OEM animators are said to make a third of their US counterparts, it’s unclear how pay has changed over the past decade.

Despite its involvement in the animation process of The Simpsons, details about the work done at Akom are scarce. A report from China Daily describes young women at computers scanning animation cells, adding colors, and putting the final technical touches to the show. Akom is the all-but-invisible magic that brings everything together.

Once Akom completes a full-color version of the episode in South Korea, it’s shipped back to the studio in Los Angeles for final review, retakes, and final edit. Shareholders give notes for revisions, and a few topical jokes are sometimes added if there’s time. The retakes division handles revisions if there isn’t time, which is a skeleton crew of two or three artists who can perform all functions of the animation process. They work on the revisions until the episode’s air date, sometimes even finishing the day or night before an episode airs.

The final editing process involves an editor working with Al Jean to incorporate the retakes into the episode, doing a final pass on the show’s colors, adding music, mixing sound, wrapping up the episode, and sending it to Fox for airing on Sunday nights. As production ramps up, multiple episodes are in development at once, and every step of the process constantly overlaps.

Al Jean, showrunner of The Simpsons, reveals that he usually knows an episode is safe and ready for air during the final mix. However, he also acknowledges that there’s always the possibility of things falling apart at any stage of the production process, whether it be during the audio assembly, animatic, or color screening. He explains that the first episode of the series was a disappointment and needed a lot of rework, which resulted in delaying the debut until the following year. But since then, they have never taken a color and not aired it, even though they have done heavy rewrites at times. Despite the occasional hiccup, the show has always managed to make it through the process and onto the airwaves. As Jean puts it, “You’re never really off the hook.”

As the process of creating a Simpsons episode is complex and involves many people, it can be difficult to predict when an episode will be deemed ready for air. According to Al Jean, the showrunner, it’s usually not until the final mix that he feels confident an episode will make it safely through the process. However, unforeseen problems can arise at any stage of production, from the first audio assembly to the color screening.

The Simpsons: Change Is Constant and Dreams Come True

One recent change to the production process was the shift to remote work for some animators due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As we discussed earlier, some animators at Film Roman, a studio that works on The Simpsons, were able to continue working on the show from home during the pandemic. This shift to remote work was challenging for the team, but they were able to adapt and continue producing episodes despite the obstacles. It’s a testament to the dedication of the team behind The Simpsons that they were able to keep the show going even during a global crisis.As the Simpsons production process has evolved over the years and with the pandemic forcing a lot of people to still work from home, so too has the technology used to create the show. One tool that has become increasingly important is Toon Boom, a digital animation software that has helped streamline the process of creating and editing animation. But even with all the advancements, the essence of the show remains the same: it takes a dedicated team of talented individuals to bring the world of Springfield to life.

One of those individuals is Chance Raspberry, a former skateboarder who used to ride past the Simpsons studio every day on his way to work. His passion for animation eventually led him to intern at the studio, where he worked his way up to become an animator on the show. Raspberry now works from home, using Toon Boom to create some of the show’s most memorable scenes.

One of Raspberry’s most iconic creations is Moe Szyslak, the gruff and lovable bartender at the heart of the show. Raspberry’s attention to detail and ability to capture Moe’s distinctive facial expressions and mannerisms has helped make the character one of the show’s most beloved.

Raspberry’s story is a testament to the power of pursuing one’s dreams. From skateboarding past the Simpsons studio to working on the show itself, he has proven that with hard work, dedication, and a little bit of luck, anything is possible. As the show continues to push the boundaries of what’s possible in animation, it’s clear that the team behind it is just as committed as ever to bringing viewers the best possible version of the show they love.