Over the past year, the emergence of AI text generators and chatbots, like ChatGPT and Bing (or Sydney), has challenged the notion that creativity belongs exclusively to humans and other living beings. While visual technologies like DALL-E and Midjourney have emerged as the counterparts to these text generators, the art world has yet to fully address this crisis.

Perhaps this lack of acknowledgement is due to a lack of opportunity. However, mega-gallery Gagosian has now opened an exhibition featuring works by DALL-E, which, like its AI image generator counterparts, can quickly transform a simple text prompt into an image. Will this exhibition bring about a crisis? Yes, it’s likely.

Bennet Miller, an Oscar-nominated film director for his works Foxcatcher (2014) and Capote (2005), is the producer of an untitled exhibition featuring works of art generated by AI. Miller has spent the past few years creating a documentary on AI, during which he interviewed Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, who granted him early access to DALL-E’s beta version before it became available to the public.

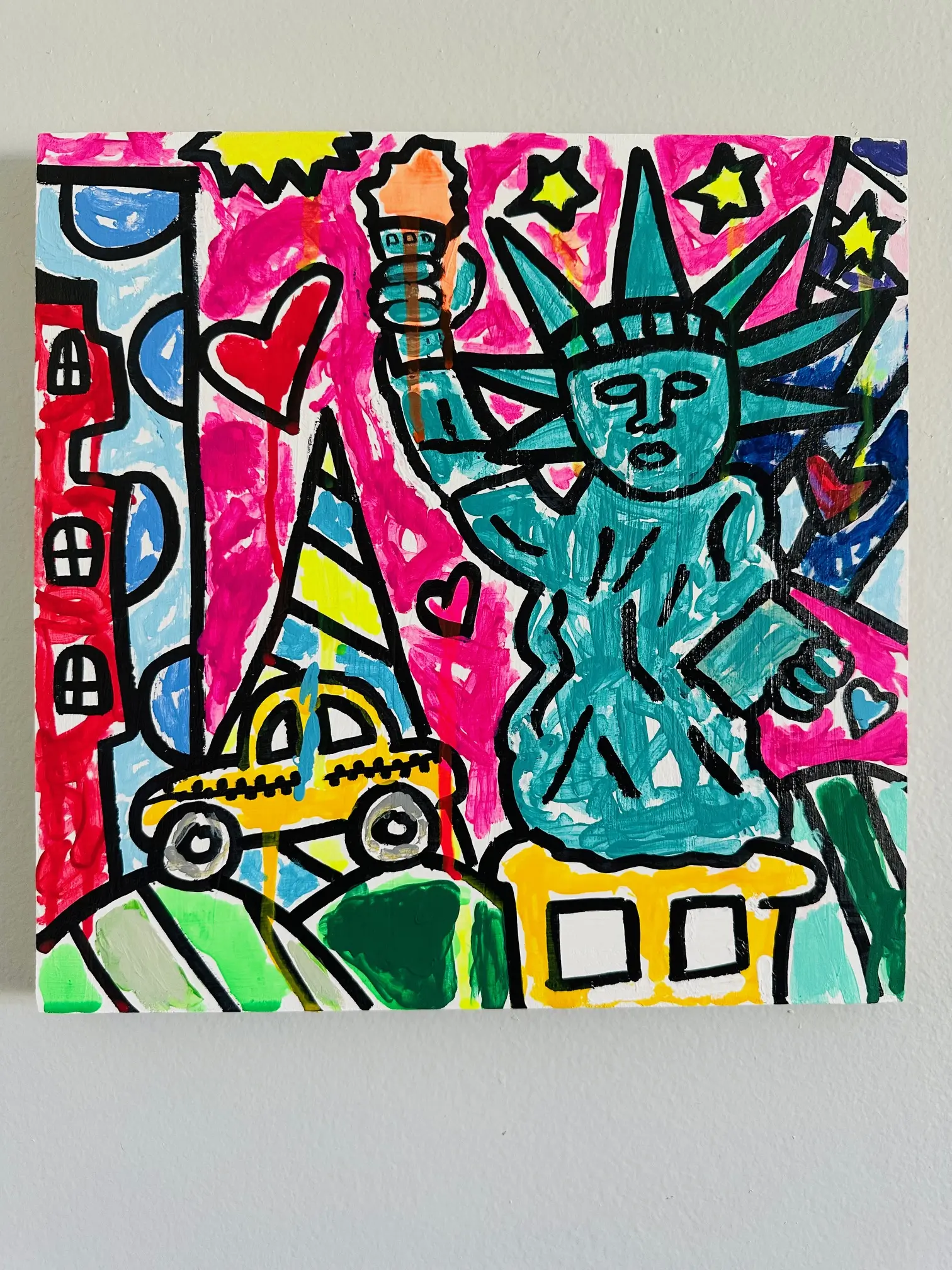

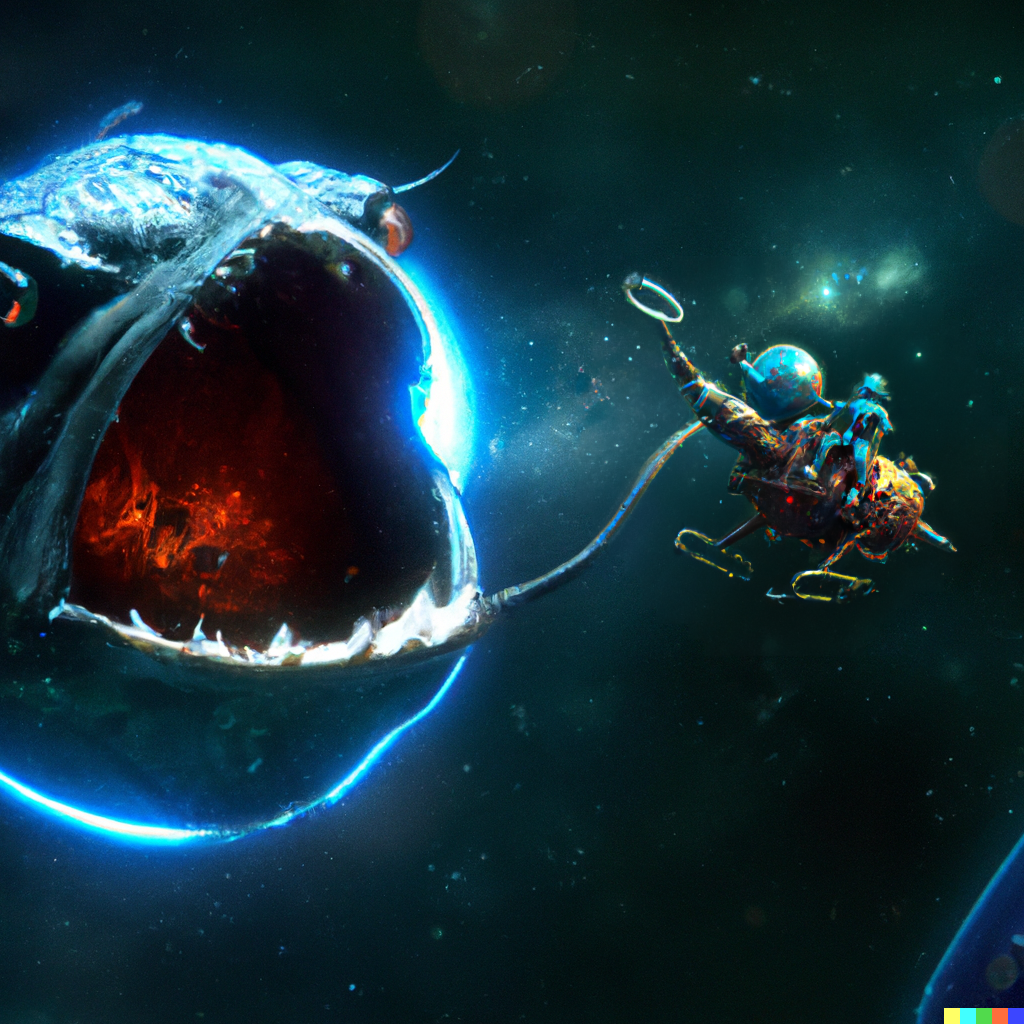

The images produced by DALL-E vary in quality, ranging from obviously flawed (twisted fingers, blurry pixels) to uncannily accurate in fulfilling the requested prompt. Despite these occasional imperfections, the AI-generated images are no longer quickly identified as such due to the absence of psychedelic patterns. This is why the audience at Miller’s opening repeatedly referred to the artworks as “real.”

From an article I read about the exhibit, while walking by, a woman points to one of Miller’s prints, a large piece with deep, wet-looking ink on sepia-toned paper. The image depicts a child staring at the viewer while her hair is tossed around by the wind. The artwork appears to be from the Victorian era, not only because of its coloration but also due to the child’s simple linen dress. However, the woman notes that it’s all a projection and tells her friend, “It’s not real.” There is no linen dress.

AI Creating Art Is Here

But, is that really important? It seems a bit dramatic to act as though we don’t already live in a world of artificiality. Furthermore, does art need to reference the real world to convey something genuine? Is “realness” even a relevant criterion for art?

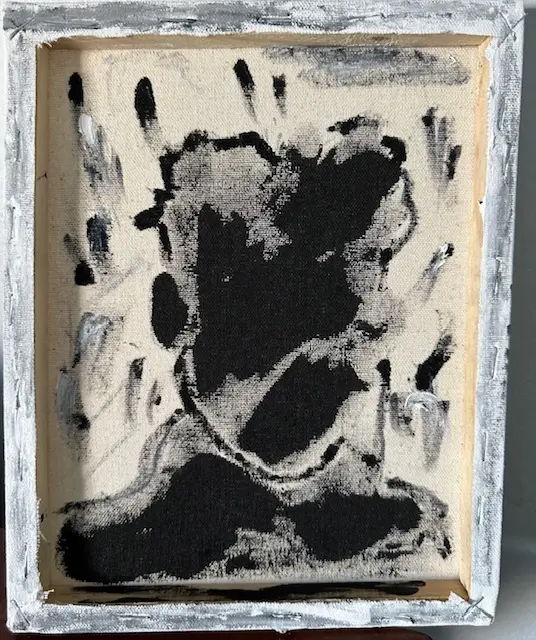

Although many of Miller’s works have a photographic quality, some are heavily stylized with a deliberate lack of focus and added grain, leaving just enough structure to hint at a subject or a landscape. Some of the images seem to depict significant or historical moments from the past. For instance, there’s a figure resembling a Native American with an extended arm that could be a wing or cultural attire. There’s also a flattened mushroom cloud as if from an explosion and a machine that looks like a train but is not quite one. Additionally, there’s a flat circular object held in the hands of a woman, deceptively simple and seemingly pointing to nothing.

Fran Lebowitz raises a thought-provoking question, “What are real photographs?” Are only film photographs considered real while digital ones aren’t? It’s a slippery slope argument; if photographers, not cameras, create photographs, then shouldn’t we also view technology guided by human minds as genuine creations? I clumsily ask Lebowitz if the labor of creating something makes it valuable. She finds my question too basic.

The question of realness arises from two concerns: the origin of these images and whether Miller deserves credit for a “real” act of creativity. In essence, the issue boils down to the presence of AI as another actor in the creative process, whose spasms gave birth to these images, curated and guided by Miller.

The term “generator” rather than “creator” for these new AI tools is revealing. Generation involves bringing something into being, but with a veil of secrecy. The concept of generation has its roots in the act of conception, which occurs without conscious thought, but rather through the hidden workings of the body. In this sense, I can relate to AI as something that creates without conscious intention, possessing the indifference and capability of nature. However, this is a false analogy. Is there a word for attributing human characteristics to nature? “Naturmorphizing,” perhaps? I’m not sure why I can’t see AI as simply an extension of other impressive technologies, all with their own hidden mechanisms.

Scrolling through images online of Miller’s exhibit, I notice that many visitors appeared happy and curious, while I feel suspicious and cautious. I scrutinize each image, ranging from vintage photographs to charcoal drawings, searching for signs of their computerized origins. I refuse to be fooled!

Many AI-generated images have a weird effect to me, introducing doors to alternate, magical worlds, revealing the yearning for the wondrous and extraordinary. But how closely is this craving for fantasy linked to the mischievous desire for deception?

We’ve all witnessed those AI-created images of Trump being arrested, haven’t we? It won’t be long before such images become ordinary, but for now, they still trip me up.